|

Contemporary Artists' Books from the New Germany Thoughts on East German bibliophily and

the artists' books of the Edition Balance

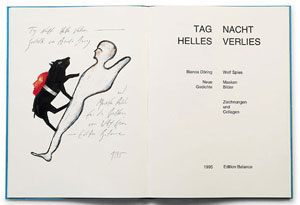

Henry Günther's curriculum vitae, who founded his Edition Balance in the former East Berlin a few weeks before reunification, obviously mirrors the discontinuity of German history. As with other writers and artists of the GDR, his life never followed a straight path but meandered and was disrupted by the social and political pressures of his time. From 1965 to 1968 he worked as an apprentice motor metalworker, one year later he started at the teachers' training college in Halle which he left as a qualified teacher for polytechnic courses in 1974. This year seems to have been the turning-point in his career: He started writing poetry, was employed as an academic assistant in the writers' union of the GDR in the specialized field of poetry in 1976, became head of department there from 1988 to 1989. Since 1980, he additionally worked as literary critic, reviewer and editor for various publishing houses and editorial offices. Beginning in 1978, he studied at the Literary Institute Leipzig, which he left with a degree in 1981. What caused him in 1974, after two completed trainings with a promising future, to found his new existence on the treacherous grounds of belletristic literature? Was it the realisation of many intellectuals of his time that the dedication to inner values is the last refuge of selfrealisation in an isolated state which allowed it, only to a certain extent, to reach material aims? Of course - the ruling classes were willing to support the established culture finanicially and institutionally, more than any government of the Federal Republic of Germany had ever done, which, of course, made it easier to come to a decision. In 1986, Henry Günther also joined the cultural underground, and from then onwards occupied himself with visual poetry and published articles in the Edition Augenweide and in the UNI / vers project outside of the public workings of literature. After a short interlude at the Berliner Ensemble (1990/91) he started working intensively as publisher and book artist since 1990: In Berlin, he became a self-taught printer and bookbinder at the Edition Sirene and the Rottmann Bookbindery, and attended courses on handmade paper and paper art at John Gerard's workshop in 1993 and in Ascona at the Centro del bel libro in 1994. The artists' book played a much bigger role in the in the culture of the GDR than in democratic states as it could be a forum for dissenting opinions because of its size, number of copies and private circulation. Thus, control through the state was made difficult. The five books that were published by Henry Günther between 1991 and 1993 are, of course, no longer subject to the control of the declined GDR, but they are rooted in it. Thus, the subtitle of the first book (Das Gleichmaß der Unruhe (7), 1991) Texte und Grafiken zur veränderten Landschaft (8) points out that it is the aim of the publisher, the authors and artists to define their position in this new Germany. Heinrich Heine's motto Ich hatte einst ein schönes Vaterland (9) becomes a central problem of a generation which has lost its Fatherland after forty years of the GDR and therefore has to ask a question about the meaning of life in the old and the new Germany. Fifteen renowned authors, among them Sarah Kirsch, Gabriele Wohmann, Kerstin Hensel, Valeri Scherstjanoi and Karl Mickel deal with this question in an elaborate way. The text of the third book Sidonie (1992) was written by Gabriele Wohmann. It details a fictitious German writer who was invited by the State Department to function as a kind of entertainer at a dinner party for the three wives of Indian politicians that are interested in cultural affairs. In the course of this conversation, the enormous uncertainty of the author can again and again be seen - she has problems with the etiquette, the mentality of the foreign guests and the choice of the appropriate topic of conversation. When she is asked to characterize her own literary theme, she says: "Problems between people, you know. Neurotic people." Finally it becomes obvious that she talks about herself with the statement mentioned before: She hates beautiful weather ("Ich bin eine Liebhaberin des Schattens") (10), suffers from the misery in the world which is seemingly ignored by the Indians ("Natürlich, sagte Sidonie, es würde keinem Verhungernden in Ihrem Land nützen, wenn Sie diesen Teller nicht halb voll zurückgehen ließen") (11) and she is only seemingly the successful author which she wants people to take her for; her flat is not - as she mentions - in the posh Ulmenhof-Allee, but in the shabby Ulmenhofstraße. In this story, Gabriele Wohmann contrasts human beings in a highly industrialized Europe who suffer from neurotic pains with the self-content members of the ruling classes in poor developing countries and in doing so, she also indirectly poses the question as to what happiness really means. The fourth book of the Edition Balance - Kants Affe. Ein Todtengespräch (1993) (12), written by Karl Mickel, is located in the 18th century and depicts a heated debate between the two extreme poles of that century - Immanuel Kant, the theoretical protagonist of the Age of Enlightenment and the noble lecher and pornographer Marquis de Sade. With this Mickel contrasts two ways of life: Firstly, the one of the rationalist, governed by reason, who accepts the responsibility to take life into his own hands after his denial of God's omnipotence and, in doing that, does not meddle in the affairs of others, and secondly, the one of the cynic who is convinced of man's inferiority, demands absolute freedom of the individual and shows in his texts the depravity of the Fin du Siècle. The texts for the second book Ausflocken (1992) and the fifth book Hans Hiob (1993) are written by the young Berlin poet Johannes Jansen, whose eruptive language in connection with changes in punctuation, falsified grammar and the consequent use of small initial letters in the volume Ausflocken portrays one of the most coherent pictures of life in socialist times. The techniques which are most often used in the five books of the Edition Balance are silkscreen prints and etchings which are used together in the first and third book and in the others separately from each other. Thus, Henry Günther takes up the graphic convention of the GDR which he links and enlargens with the complicated technique of the etching. In doing that he breaks with the "bibliophily of poverty" which was typical of some private presses of the GDR and arranges his books in the long tradition of superbly produced private press and artists' books. In the second book the aesthetic feelings are even more heightened because the pictures by the artist Wolf Spies are original drawings which turn each of the 35 copies into a unique work. Henry Günther, nevertheless, does not make the error of simply wanting to produce a beautiful book by using a text which has been published often already, where no copyright problems exist, and which is only a cause for being beautifully printed, illustrated and bound. All texts of the Edition Balance are principally first editions. All of these texts are critical, difficult, some even bulky and far from everything which bibliophile collectors would like to read in their refuge. But are other texts justified in a world which seems to be out of joint? The pictures that go together with the texts - and this, too, is typical of the books of the Edition Balance - integrate (in three out of five books) the text into the picture which means that the word, in the end, becomes the picture, the picture itself the word. In the book Sidonie Guillermo Deisler depicts the suspense between the people, the figures themselves in nervous and distracted strokes in his etchings and silkscreen prints; the same strokes, however, also write the text into the pictures. The text loses the character of something being written, something making sense, something that can be read and is transformed into a picture until the written word and the picture possess the same qualities. It is this transformation that transports the word into the realm of the picture and thus makes it accessible to other layers of consciousness. Johannes Jansen, who created the pictures for his own text Hans Hiob, follows this principle. The letters constitute a head where the world of images and words comes alive and which mirrors the geography of the soul in an Arcimboldesque way. The structure of the lines is reminiscent of CAD-graphics which furthermore links the silkscreen prints to the imaginary world of virtual reality. The pictures in the books of the Edition Balance therefore tell their own stories which are based on the text, even use it for the overall design, but nevertheless preserve their autonomy. Thus it makes sense to occupy oneself with these works of book art even for someone who does not have a good command of the German language because each book is open to different interpretations and imparts messages that break through the boundaries of language with vehemence and passion - stories without any words. Reinhard Grüner Annotations

|

The decline of the Tausendjährige

Reich

The decline of the Tausendjährige

Reich